"I don't create anything. I assemble, I steal here and there, to make - with what I see, what the dancers can do, what others are doing".

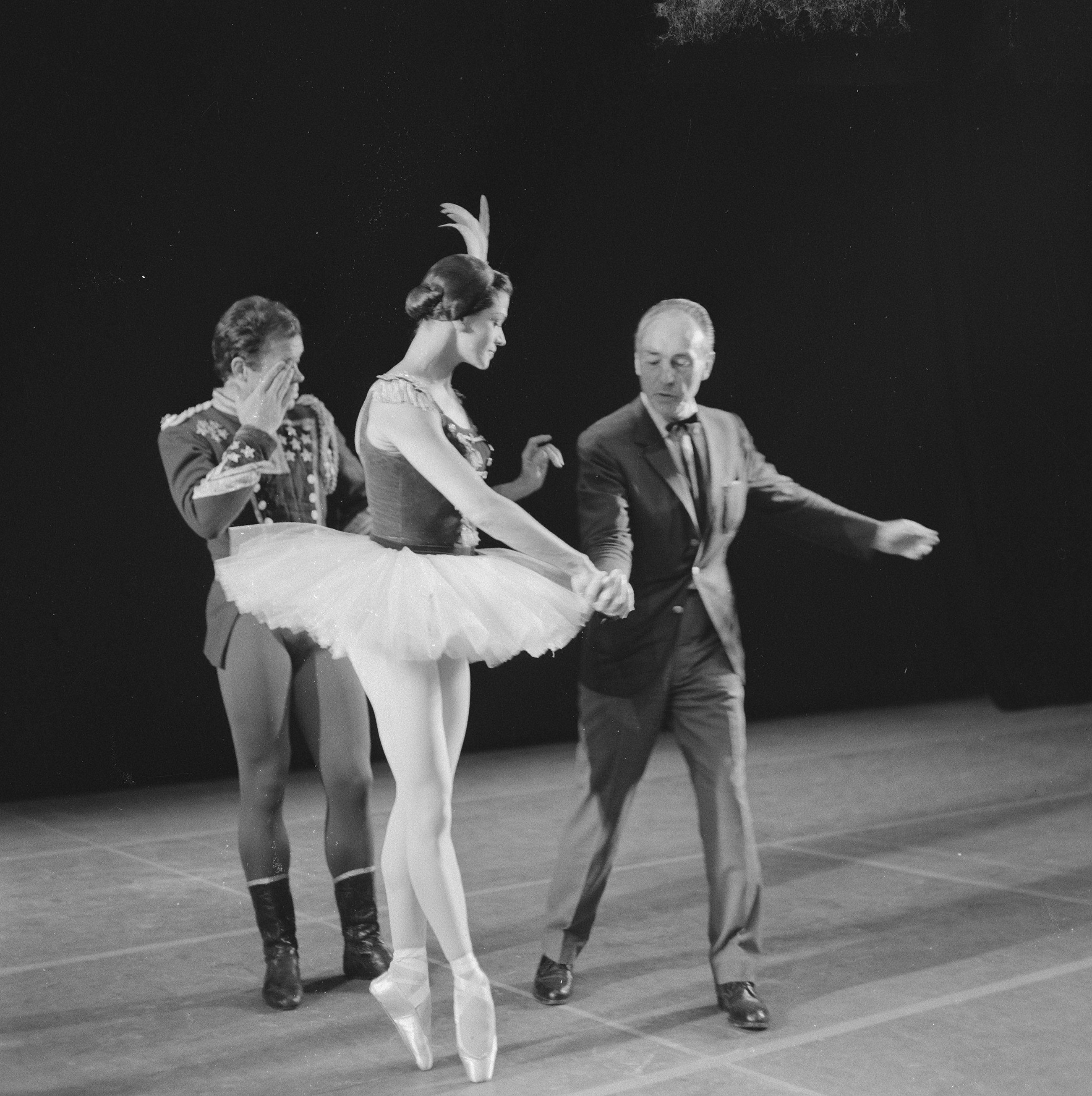

The choreographer who speaks through this quotation is George Balanchine, a man who would leave his mark on the 20th century with his vision of bodies: corps de ballets, dancer bodies, whom he would train in large numbers in his ballet school. Also trained as a pianist and musicologist, the relationship between ballet and music was crucial to him, and he left his mark on the world of written music through his friendships with the great composers.

It was this lover of Tchaikovsky, close friend of Gershwin, and founding choreographer of the New York City Ballet alongside Jerome Robbins, that Crédit Agricole CIB invited you to discover on February 16 at the Palais Garnier through two ballets: Imperial Ballet and Who Cares? What better prelude to the evening of November 09, dedicated to his audacious colleague, than a look back at this legendary figure of the dance world?

George Balanchine was born in St. Petersburg in 1904, and inherited a family predisposition for music: his mother was a ballet lover, his father a composer. His brother and sister also shared his passion for music. He himself did not seem overly interested until 1915, when, aged just eleven, he danced for the first time in Sleeping Beauty (track 1), a ballet choreographed by Marius Petipa. From that moment on, the young Giorgi gradually discovered a passion not only for dance, but also for music! Parallel to his studies with the Imperial Ballet of St. Petersburg, he pursued brilliant studies in piano and musical erudition, which led him all the way to the Conservatoire... But in the meantime, revolution broke out in Russia. The Bolsheviks in power undermined the budget previously granted to cultural institutions, and censored the initiatives of young artists - such as the Young Ballet, formed in 1923 and almost immediately disbanded under pressure from Mariinsky Theatre bureaucrats. The following year, his twentieth, Balanchine set off on a tour of Europe, from which he would not return until fifty years later: after defecting with other dancers, he met Serge Diaghilev in Paris and joined the Ballets Russes under his direction. Diaghilev also gave him the opportunity to choreograph several productions, aware of the talent hidden behind the dancer's virtuosity. But Balanchine needed more than this to set him on the path to his future career: in 1925, a knee injury forced him to stop dancing. After Serge Diaghilev's death, he continued to choreograph numerous ballets, collaborating throughout Western Europe with great names in music and theater: Ravel (tracks 2-4), Weill and Brecht (track 5)... Then, in 1933, he received an offer to set up a company on the other side of the Atlantic. At just twenty-nine, the virtuoso choreographer arrived in the United States.

The years that followed saw him take off: he moved to New York, founded the prestigious and demanding School of American Ballet, and became ballet master of the Metropolitan Opera; George Balanchine reigned over the world of American classical ballet. After conquering the East Coast, he set off to explore the West, in particular Los Angeles, where he formed a new company, Ballet Caravan. It was for this new troupe that he choreographed his masterpiece Imperial Ballet, a setting of Tchaikovsky's Second Piano Concerto (track 6), and Balanchine wanted to assert himself in the eyes of the world as the heir and spiritual son of Marius Petipa - the notorious choreographer of Tchaikovsky's scores - and in whom he had so immersed himself during his studies. He tried to get closer to the phantasmagorical atmosphere of his childhood memories: St. Petersburg under the Tsar's reign, the great imperial buildings that he could only remember - Balanchine would not return to his native country until the end of his life, a passing visit insignificant in relation to the composer's love for him. Imperial Ballet was created in 1941, in the midst of the Second World War, when Nazi Germany dropped its masks and began its offensive against the USSR, and the USA entered the war. Balanchine would later revise it extensively, removing or adding details, modifying steps - a notable change being the deletion of the double saut de basque, present on several occasions in the original choreography. It was also at this point that he renamed it Tchaikovsky Piano Concert n°2. Even today, the changes are far from unanimous, and many companies choose to keep the first version and its name.

Classical or jazz, ballet or contemporary dance... in fact, in parallel with his career as a choreographer in classical ballet, Balanchine took a keen interest in jazz and popular music! He discovered Fred Astaire, whom he considered an exceptional dancer:

"You find a bit of Fred Astaire in everyone's way of dancing - a pause here, a movement there. That was Astaire's originality.”

He went on to write three choreographies for Broadway. His love of seemingly popular music is also evident in Circus Polka, for dancers... and elephants, with music by Igor Stravinsky (track 7), one of the choreographer's most important collaborators - another Russian in exile, another avant-gardist he met in Europe in 1928 and with whom he wrote over thirty ballets (tracks 8-12)!

The twenties saw another discovery that led Balanchine to transcend the dichotomy between "classical" and "popular": George Gershwin, a composer close to jazz music and the Broadway scene. The film Goldwyn Follies (track 13), released in 1938, was the occasion for a collaboration between the choreographer and the composer (unfortunately short-lived, as Gershwin died of a brain tumor during filming). More than twenty years later, Balanchine, playing piano on a songbook, imagined a choreography based on a suite of songs composed by Gershwin. He commissioned an orchestrator, set to work and, in 1970, produced Who Cares? (tracks 14-15) The title sets the tone: in the words of one critic,

"it takes extreme self-confidence, or critical confidence, to call a ballet Who Cares?”

Who Cares is the lightness of New York, of Broadway:

"It's an attempt to evoke a world of warm nights, cool martinis, where [Fred and Adele] Astaire look at each other smiling in a spirit of joyful camaraderie," the critic continues.

The music is indeed light - as is the orchestration, which was only completed a few months after the premiere: the latter was performed with the first and last pieces in orchestra, and the entire middle section played on piano! With the exception of a touching tribute in the form of a recording of Gershwin at the piano, "Clap Yo' Hands" (track 16). Gershwin, who had long been eclipsed by the ballet, was reinstated in 2010. Balanchine died ten years after the first performance of Creutzfeld-Jakob disease, diagnosed only after his death.

From Imperial Ballet to Who Cares?, from Tsarist Russia to the glittering nights of Broadway; at first glance, it might seem logical to emphasize the opposition between the two ballets, the tradition and framework of Russia versus the freedom of the United States. But in the end, aren't they two sides of the same coin? In other words, the choreographer's lifelong attachment to memory and remembrance.